What’s my age again?

There’s a game some people like to play whenever Coachella unveils the lineup of that year’s festival. You can work out your “musical age” by subtracting from 80 the number of names you recognise on the poster.

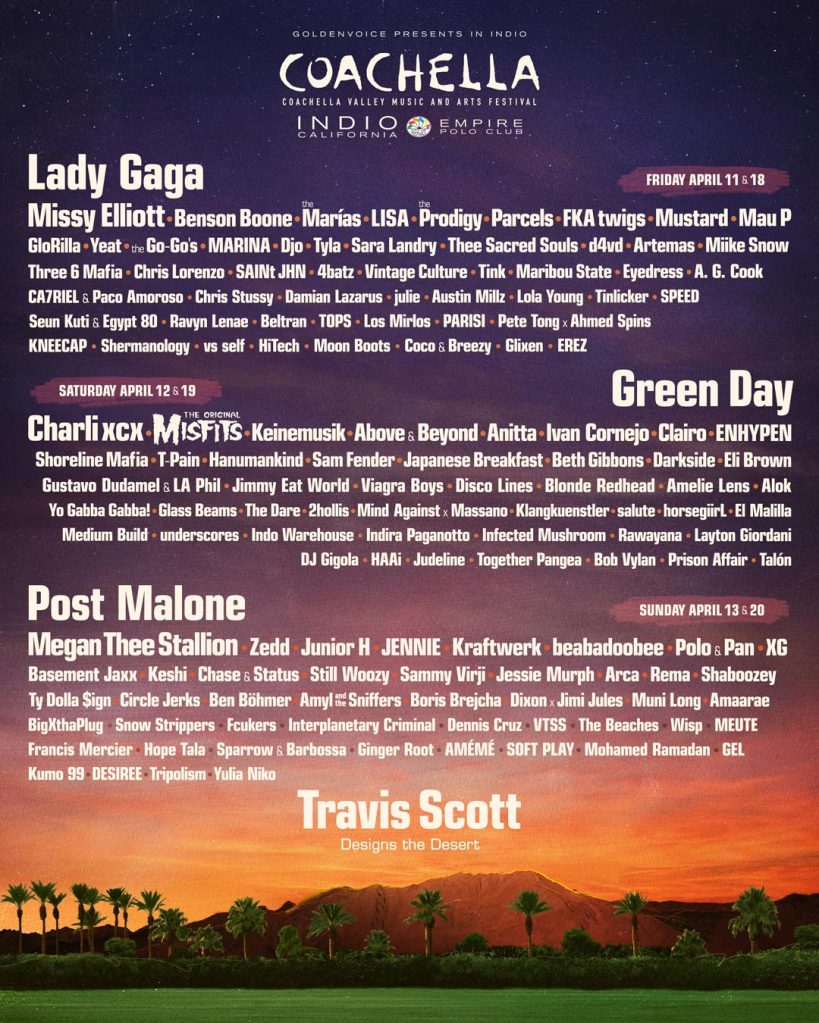

Based on the 2025 poster, my musical age is 46. But if I were to calculate it based on the number of acts I’d be interested in watching… hmm!

See for yourself:

The higher your “musical age”, the more you might relate to what follows.

Mud and Thunder, Sun and Polo

Coachella’s roots lie in a big gig Pearl Jam put on at the Empire Polo Club in Indio, California in 1993, when they were boycotting various venues due to a dispute with Ticketmaster. Paul Tollett, the man behind Coachella, considered that a site that could host a riotous Pearl Jam gig could also feasibly host a righteous festival. An indie festival in Indio – why not?

So, if one were to argue that Coachella has forgotten the face of its father, as one might, then the face in question is that of Eddie Vedder.

It would take six years for these initial seeds to flower into a festival. It’s hard, after all, to make anything take root in the desert. Tollett and his team apparently spent a lot of the intervening time trying to sell people on the idea of attending a festival a million miles from anywhere. They handed out flyers at the 1997 Glastonbury Festival – one of the muddiest ever. “We had this pamphlet I was giving out,” Tollet said, “showing sunny Coachella. Everyone was laughing.” I bet they were.

The New Yorker described the original idea behind Coachella as follows:

“In creating Coachella, Tollett took the best aspects of the indie-rock, jam-band, and SoCal rave/dance nineties festivals, added the large art installations of Burning Man, and grafted this new festival hybrid onto the original hippie rootstock—the sixties-era longing for a new world which three days in the desert helps satisfy.”

Tollett has described his intentions for the festival as follows:

“We wanted it to be far. So you surrender. So you can’t leave your house and see a couple bands and be back home that night. We want you to go out there, get tired, and curse the show by Sunday afternoon. That sunset, and that whole feeling of Coachella hits you.”

It was to be more than a bunch of bands playing in a field. It was to be a destination. A trip. A spiritual, transformative experience.

Keep this in mind.

In a profile that describes Tollett as a “desert music magician”, our man says that the idea behind the original Coachella was “to book a lot of cool bands that weren’t very hot on the music charts. Maybe if you put a bunch of them together, that might be a magnet for a lot of people.”

Emphasis mine. Again, keep this in mind.

Party Like It’s 1999 (Because It Is!)

The inaugural Coachella was announced the week the disastrous 1999 Woodstock Festival took place, and it presented itself as the anti-Woodstock. In place of the searing concrete, the riots, the arson, and the angry nu-metal, they promised green grass, cool water, proper bathrooms, and lots and lots of good vibes (and Morrissey).

Irresistible. But there was one problem: They announced this brand new festival, which was to take place in October, in August. Would-be attendees had just sixty days or so to get themselves together.

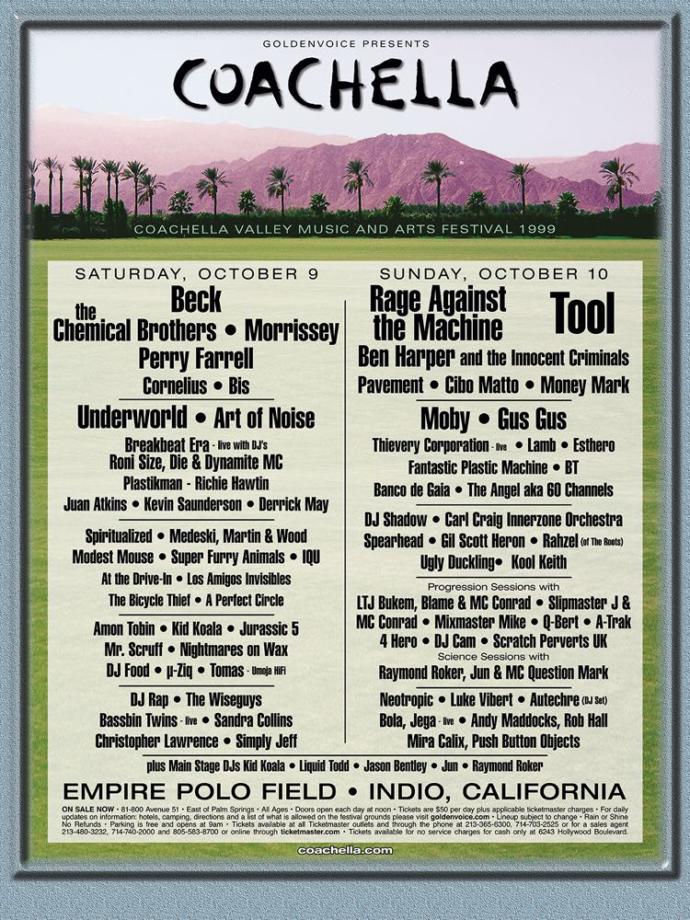

The first Coachella was a financial disaster. It was also very, very hot, with temperatures reaching up to 41°C. But oh, the lineup. Good vibes only, please. And Tool. And Rage Against The Machine. And Morrissey:

There would be no festival in 2000, and Tollett sold his house and his car to make the 2001 event happen. And once again, look at the state of it:

Imagine watching The Orb in an air conditioned tent in the middle of the desert, having just swayed your way through Sigur Rós and brooded along to Tricky. This is the sort of thing that used to happen.

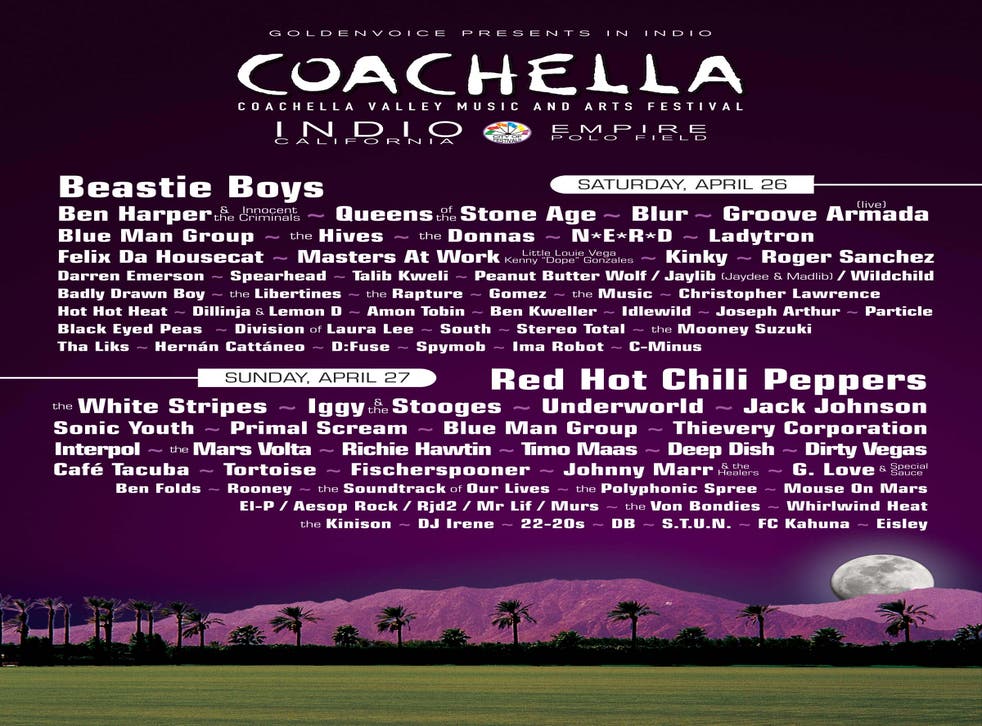

And dig the 2003 Coachella. You could watch the blue paint drip from the Blue Man Group as they struck their pipes in the desert heat, before grooving to Gomez in their In Our Gun prime. Oh, and you could also see a reunited Stooges – it was at this festival, I believe, where they made their post-reformation debut – on the same stage as The White Stripes, Sonic Youth, The Mars Volta, The Polyphonic Spree, and The Soundtrack of Our Lives – on the same day:

Change, and a Caveat

Coachella finally grew into a three day jamboree in 2007. In 2012, it became a monster: The same three-day-festival, twice, across two successive weekends, with essentially the same lineup each time.

So Coachella got big, eventually. But at what point did it become bloated? And by “bloated”, I of course mean: “Unappealing to me, personally.”

I’m treading carefully here. Because, who am I to imply that Coachella has lost its way? It’s obvious that I’m not their target audience, and I haven’t been for a decade or more. But beyond that, I have never been to Coachella. I don’t know what it’s like. And most important of all, I am not American. America is a foreign country. That which strikes me as bland or dispiriting might, to the American mind, appear bodacious and tubular.

But who could deny that the festival is not what it was? Whether you feel it’s changed for better or worse, it has changed.

This is not the story of a rock festival that slowly became something else. From day one there were more turntables than guitars, and Coachella has always been a rapper’s delight.

No, this is the story of a glittering tributary, which brought life and greenery to the desert, flowing into the mainstream with its arid banks. It’s the story of a charming jalopy, held together by duct tape and goodwill, changing the radio station as it gradually drifts into the middle of the road.

And I wanted to find out when this happened. So I did what I always do in these situations. I listened to every band, artist, and DJ on every lineup, in order. It’s a good system: The point at which I get bored is the point at which the decline begins. And usually, there’s a point where things get unbearable. That’s the Rubicon moment. The point of no return.

So When Did Coachella Lose its Groove?

Some might say it happened as early as 2005, when Coldplay headlined. I would not.

In 2005, Coldplay were still an arena rock band. They were still “indie-coded”, if you will. It’s only in recent years that they’ve committed to that Bill & Ted mission, of trying to achieve world peace by writing a song for everyone. And alas, through attempting to broaden their appeal to everyone on the planet, they’ve flattened everything that made them so loveable in the first place. Coldplay’s trajectory parallels Coachella’s. But they’re not the band that en-blanded Coachella.

In 2008, Coachella started letting giants headline. First Prince and Roger Waters. Paul McCartney would follow in 2009. Kings. Legends. Major coups, for Coachella. But stakes raised, the likes of Beck and Bjork would never be allowed to headline again. Suddenly, they were too small.

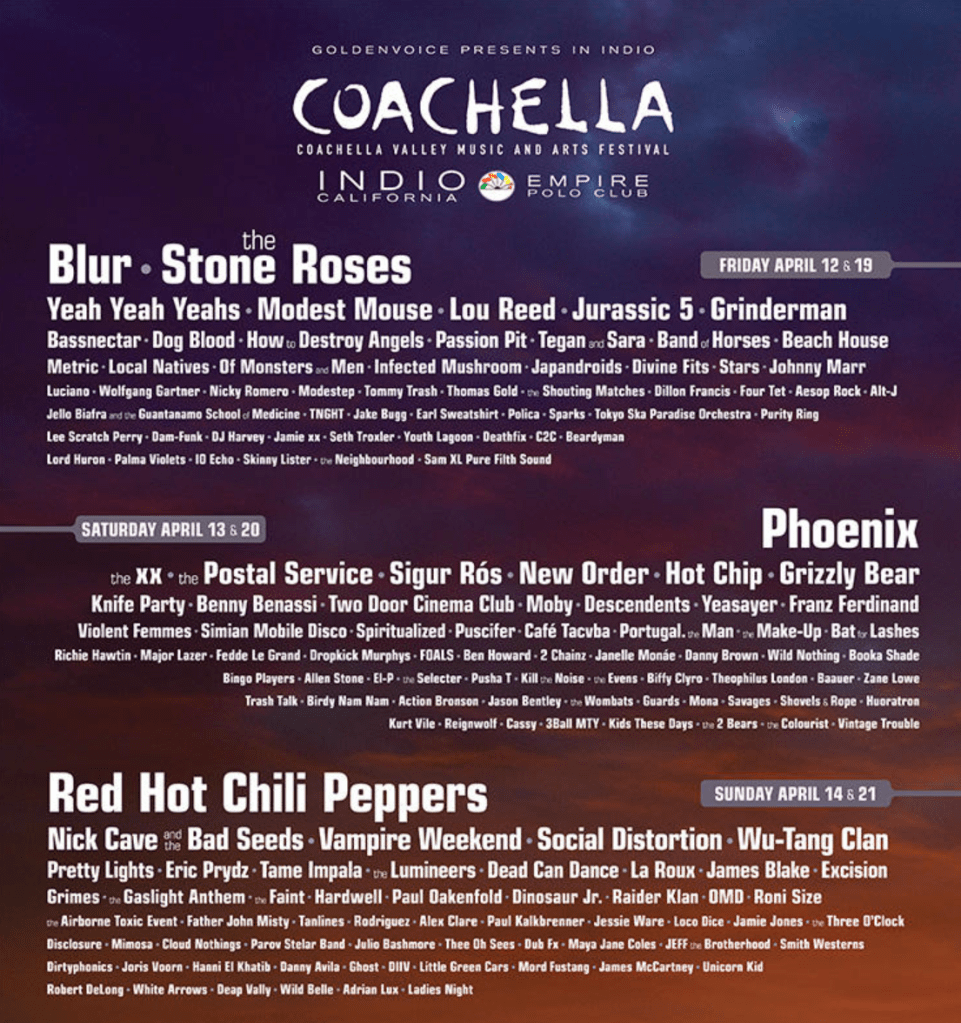

Coachella 2013 was indie’s last stand. Blur and The Stone Roses co-headlined, and apparently the latter performed to a largely ambivalent crowd. Phoenix, too, took the top spot, the sort of thing that will probably never happen again.

The 2015 festival was headlined by a couple of dependable crowd-pleasers – Muse and Arcade Fire – along with Outkast, who were then making a triumphant return. But the 2016 and 2017 festivals revealed what was to come. The Weeknd and Drake led the charge in 2016, and Calvin Harris twiddled his knobs on the mainstage in 2017. From this point on, barring one last Radiohead set, Coachella headliners would now be almost exclusively rappers, pop stars, and DJs.

Do not get me wrong: Rappers, pop stars, and DJs absolutely deserve to headline festivals, and may nothing but happiness grace the doors of all who listen to them. And kudos to Coachella for keeping things fresh. Moreso than perhaps any other festival, they seem determined to take risks, and to let artists headline who have never headlined before.

Yet in focusing on what’s popular, above all else, I cannot help but feel that Coachella has lost its way. Remember the ethos behind that initial festival in 1999 – to create a happening in the desert with the help of the critically acclaimed, and not necessarily the commercially successful. I’m not about to suggest that Coachella’s lost that loving feeling, as Tollett and co. obviously put their hearts and souls into this thing. But still: Where’s the love?

Who Gets to Play Coachella?

In his long New Yorker profile, Tollett described, in some depth, his criteria for choosing who plays Coachella. It’s all about what’s hot, and what’s not. And this, unfortunately, largely seems to boil down to social media metrics.

Compare this to the very first Coachella which featured, as The LA Times noted, “a bevy of artists who were picked more for their critical acclaim than for commercial success.”

In this same contemporary account of the 1999 festival, we learn that:

“The Coachella organizers say they politely turned down some “name” bands that could have pumped up the marquee value but would have clashed with the cutting-edge sensibility. The bill also has an unusually large number of artists who don’t have new releases out, another nod to the goal of assembling a show highlighting art, not commerce.”

Art, not commerce. If you want to summarise how Coachella has changed, in a single sentence, just flip those two nouns. Coachella began by offering attendees the opportunity to get it together, in the desert. What do they offer now? An opportunity for influencers to take a selfie in the desert?

In his New Yorker profile, Tollett also talks about the sort of things he thinks his attendees want to hear. And this, to me, makes for particularly grim reading:

“When you take an indie-rock band, five or six members, not everyone is on the E-flat seventh at the same time, so it doesn’t sound perfect. With electronic music, it’s pre-programmed, so it sounds flawless. There are no mistakes. There’s a generation that’s used to flawless, and when they don’t hear flawless it may suck to them.“

“There is no underground anymore,” he added. “It’s all kind of pop.”

This is just what major festivals need to do in order to survive. The counterculture slowly died between 2006 and 2016. In this world without an underground, countercultural festivals have either perished, or they’ve mutated into something unrecognisable. Only those festivals that cater to evergreen niches, like metal, have been able to stay true to themselves.

I never used to like the term “alternative”, as a music genre. I used to think, alternative to what?

At least now we have our answer.

The Desert Needs a Beer!

As I listened through the Coachella lineups, I made a playlist. It’s a work in progress. When it’s done, it will feature most of the acts that played every Coachella up to and including the 2009 festival, with a few choice selections from the later lineups.

There are plenty of bangers here. But when choosing the songs for this playlist, I found that I was often drawn to chilled vibes and beatific beats. I kept picturing beautiful people dancing under a crimson sunset as the desert mountains glowed purple in the golden hour.

Give it a listen. Beer is optional, but good times are essential: