I’ve decided to revive the NAGCHAMPA project.

Reminder: NAGCHAMPA = New Age Grammy Challenge: Healing Assessments of Musicians Perceived as Awful.

Following my foolhardy metal quest, I feel like I need some quiet and visionary music as badly as I sometimes need a cup of tea and a flapjack.

It’s been five years. But if you remember, I’m studying every album that ever won the Grammy Award for Best New Age Album, in an attempt to understand what makes New Age Music so New Age. The closest I came to a definition was this: New Age Music is applied ambient music. Or, it’s spiritual ambience. It’s music that aims to make you feel better, and succeeds.

But while my back was turned, the Grammy guys broadened the scope of this awards. Since 2023, the category has been “Best New Age, Ambient, or Chant Album”.

“Ambient” I get, but “chant”? Will there be chanting? Was there always chanting?

I swear, I had no idea that the 2025 Grammy Awards were taking place as I wrote this thing. The BBC didn’t even include the New Age category in their roundup of the winners. It looks like it went to Wouter Kellerman, Eru Matsumoto, and Chandrika Tandon’s Triveni. A worthy winner? We’ll see, when I finally get to 2025 in this project, some 16 years from now.

Because we’ve only just made it to 1994 here, and it’s Paul Winter’s time to shine.

Paul Winter has won more New Age Grammy Awards than anyone else. He’s won six times in total: Twice as a solo artist, and four times as the leader of his consort. His 1987 album, Canyon, was nominated for the inaugural New Age Grammy. We also enjoyed his Down in Belgorod project in 1989, his Icarus in 1990, and his Earth: Voices of a Planet in 1991.

After four nominations, and having been beaten to the post by, in turn, Andreas Vollenweider; Shadowfax; Peter Gabriel; and Mark Isham; in 1994 Paul finally got his gong. About time too. I believe that Paul was robbed of the 1987 New Age Grammy. That’s right: ROBBED!

Paul Winter is an American saxophonist who likes to improvise in natural settings. Many of his albums seem to feature just Paul, alone in the middle of a wide open space, playing his horn to his surroundings in the hope that they’ll harmonise. They usually do.

Spanish Angel, though, the album for which Paul finally won his Grammy, is a group effort. The Consort is an all-acoustic sextet that includes three horns – Paul says he views both the flute and the cello as a horn – and a rhythm section incorporating piano, guitar, double bass, and percussion.

Spanish Angel is a live album. So, not only do we get to hear Paul’s considerable talents as an ensemble musician, we also get to hear him playing to an audience beyond the birds, the bees, the rocks, and the trees.

This is compiled from a number of performances from The Consort’s 1992 tour of Spain. Here we hear recordings from Cádiz, Madrid, Almería, Vigo, Salamanca, and Cartagena. They played in theatres and concert halls, yet this doesn’t sound like it was recorded indoors. It sounds like it was recorded in a forest grove at dawn, as the squirrels stretched, yawned, and brewed coffee, and as the first rays of sunlight began to poke through the leaves to scatter tiny arcs of light on the undergrowth. But is the Sun rising in time with Paul’s playing, or because of it?

For Paul’s sound is aural sunlight. The Winter man brings the spring. Leaves and flowers sprout in his footsteps, and as he plays colourful shapes dance and spiral in the air. By the time he’s done, it’s summer.

But he’s not the first thing you hear on Spanish Angel. The selection opens with Rhonda Larson’s flute, as part of a performance that would be Rhonda’s last appearance with the Consort. It sings like joyous birdsong. But Paul’s soprano sax starts to shine from around the three minute mark. And from that point, it’s really all I want to hear.

These are masterful performances, and everything comes together to form a beautiful, radiant whole. Yet though he frequently lets others solo (Rhonda’s flute is wonderful throughout), Paul’s mellifluous soprano sax sound always rises to the top, like the rich cream it is. Picture a thread of gold woven through a rich tapestry. Even if you step back to admire the pattern as a whole, the shimmering gold still catches the light and shines the brightest.

This music’s always moving. Throughout, you’ll hear rhythms that evoke the swaying of boats on water, and recordings of wrens as “invocation and benediction”. There’s an improvised cello-piano duet, a “melodic party in 5/4 time”, and a tribute to the Sun’s energy, with a buzzing Moroccan bendir drum replicating the dance of “quintillions of tiny, whirling particles”.

Winter’s Dream, which Paul makes clear is not HIS dream, is the most understated piece here. It’s just Paul and a piano, conjuring the deep sigh of the Winter Solstice. “The dream is for renewal,” wrote Paul, “following the tradition of ancient solstice rituals which at this darkest and coldest time of the year, beseech the sun to return.” Well, Paul, if anyone can bring the sunlight, it’s you – even if this dream sounds a bit like the theme to Pet Rescue.

Music For a Sunday Night in Salamanca is an interesting one. According to the liner notes, at this point during this particular concert (in Salamanca, yes), the group requested total darkness, to allow them to “play whatever [came] into out collective imagination.” The result they describe as a “free polyphony”, or “our own kind of Dixieland”. To me it sounds like the process of creation itself, a slow evolution from murky mysterious beginnings to fizzy enlightenment. You can hear the spark of inspiration, when it hits. It’s astounding what’s possible when selfless, sympathetic players with superhuman talent improvise. It provides strong evidence for the existence of telepathy.

It ends with some further improvisation – Blues For Cádiz – which apparently sprung from a blues riff Eugene Friesen started playing on his cello when the audience started clapping in a 6/8 Flamenco rhythm. Rhonda the flautist growls some impromptu vocals, which sound like the Cookie Monster eyeing an oven fresh batch. This was the final moment of her final performance with the band, which Paul described as “an appropriate ‘trickster’s’ coda.” She was known for her sense of humour, he sighs.

“Immersed in the stream of all this music,” Paul wrote, “time seems to disappear, and I feel a part of one grand, ongoing community, celebrating life with sound.” He’s specifically referring here to the lineage he’s detected in the compositions of his various bands over the years. But in doing so, he’s also described this miraculous recording perfectly: It’s a beautiful celebration of life, with sound. Paul Winter: Worthy winner.

Other Nominations For the 1994 New Age Grammy

Clannad – Banba

Clannad likely thought they were a shoe-in for the 1994 New Age Grammy. After all, the previous year’s award had gone to Enya, who’s related to the two siblings and the two uncles that comprise Clannad. She even used to sing with them! Ah, but you don’t bet against Paul Winter. Not even if you’re New Age Royalty.

Banba is an Irish goddess who is said to travel with a “troop of faery magic hosts” in the Tochomlad mac Miledh a hEspain i nErind: no Cath Tailten. Some of the songs on this album are worthy of this portentous name. They evoke misty mountains, enchanted dales, and soil that sparkles with earth magic. Other songs sound like classy Celtic pop, complete with snazzy sax lines to make those classy Celtic cocktails go down easier. It’s all boss, though. Come for the mysticism, stay for the theme from The Last of the Mohicans.

Ottmar Liebert + Luna Negra – The Hours Between Night + Day

Dig those plus signs! Much more de rigueur than “and” or, let’s face it, an ampersand. This is the sort of thing that happened in the 90s. See also, Baz Luhrmann’s delirious Romeo and Juliet adaptation, which he titled Romeo + Juliet. The plus tells you what to expect: Shock!

For an album that uses the same edgy font as those “you wouldn’t steal a car” anti-piracy ads on its cover, The Hours Between Night + Day is seriously chilled. Ottmar Liebert is a German guitarist who plays in a controversial “Nouveau Flamenco” style. He picks his lyrical licks while his backing band, Luna Negra, provide some urbane grooves, some enthusiastic handclaps, and the occasional soothing synth tones. Sometimes there are vocals, sung in such a way that suggests Ottmar’s carefully wiping a tear from a newborn deer’s eye with a handkerchief tied to the end of his guitar.

Tangerine Dream – 220 Volt Live

Tangerine Dream is more of an idea than a band. Edgar Froese was a constant, but the group decided to keep going after he passed in 2015. They’re now on their 29th lineup. Their oldest member wasn’t even born when the band first formed, and their current bandleader only joined in 2005. I’m not saying this is a bad thing. The world needs cosmic music. But is there any other band that operates like this? Will the inhabitants of Mars Base Zeta still be listening to new Tangerine Dream releases in the year 3000?

220 Volt Live, the group’s 48th album, was recorded during Tangerine Dream’s 1992 US tour. Edgar’s son, Jerome, who appeared on the cover of such classic album’s as 1973’s Atem, contributes keyboards and guitar. Zlatko Perica plays lead guitar, and Edgar himself picks up the axe at some points too.

The result is over 70 minutes of keening guitars over electronic drums and aspirational sequencers. In their 70s heyday, Tangerine Dream made visionary music for alchemists, stargazers, and wizards. This is music for a different kind of magician – the mulleted sort with a Las Vegas residency who makes elephants disappear right before your eyes. It’s by no means bad, but it does sound like a poor man’s Ozric Tentacles, and it does contain the naffest cover of Purple Haze you’ll ever hear.

The Seth Man, writing on Julian Cope’s Head Heritage site, once wrote that Tangerine Dream’s 1975 album Rubycon is aptly named, for it’s a line you should only cross at your peril. Personally, I’m willing to listen to anything with the Tangerine Dream name attached to it. But stuff like this makes it clear that one should always tread carefully when navigating their labyrinthine archives.

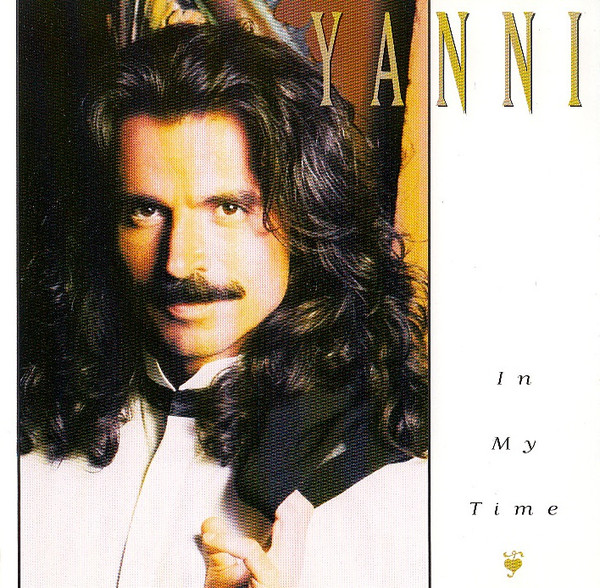

Yanni – In My Time

Finally, some more Yanni.

By which I mean, “the final album in the list of album’s nominated for the 1994 New Age Grammy is a recording by Greek musician Yiannis Chryssomallis”; not “at last, some more music from Yanni!” Though rest assured, my friend. I am very pleased to see Yanni’s luxurious moustache again.

For this album, Yanni wanted us to “feel the human being behind the music.” And what a human being he is. Look at him there, with his smouldering eyes and his jacket slung over the shoulder. Sheer romantic POWER. And this is music for human connection – for lovers. There’s sparse background instrumentation, usually in the form of quiet, tearful strings. Mainly it’s just Yanni, and his piano, and his moustache.

I can imagine getting seriously wistful to this music if I listened to it on a grey, aching, regretful morning. Yanni plays beautifully, soulfully, perfectly. But it’s hard to shake the impression that this was recorded for candlelit dinners, and all that would follow. I would not advise playing this in such a setting. They’d probably run even before you emerge in your kimono with the dragon pattern.

NEXT TIME ON NAGCHAMPA: More Paul Winter! More Tangerine Dream! And a Monkee!